Under Construction

“Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.”

I see it.)

The ‘Sixties!

When the Living Theatre left for EuropeBacktracking to 1959, one will recall that, after a dozen years producing classics and European avant garde works Off Broadway, The Living Theatre shocked the establishment with Obie Awards for their first original play, The Connection—itself a theatrical milestone—and in 1963 for The Brig, a scathing attack on military prisons that prompted their arrest and three-year exile overseas.

More to the point, among Living Theatre ensemble was Joseph Chaikin, an award-winning young actor who, when the Becks hightailed it off to Europe, stayed behind to hold the fort, and thus became the guru of the Revolution in American theatre and, arguably, the unsung Father of the Anti-Establishment Movement.

The youngest of five children, Chaikin was born to a poor Jewish family living in the Borough Park residential area of Brooklyn. At the age of six, he was struck with rheumatic fever, and complications led to life-long heart problems. At ten, he was sent to the National Children’s Cardiac Hospital in Florida, where he spent two years developing his dramatic gift, creating theatre games to play with the other children.

He spent his teenage years in Iowa, his family having relocated, and briefly attended Drake University before returning to New York to launch a career in theatre. Like thousands of others, he struggled to survive, working a variety of jobs, and gradually began to be cast in legitimate stage roles before joining the Living Theatre in 1959. He was in the casts of both The Connection and The Brig, and won an Obie for his performance as Galy Gay in Brecht’s Marxist play, A Man’s a Man in 1962.

In 1963, he and playwrights Peter Feldman, Megan Terry, and a very young Sam Shepard, founded the Open Theatre

The Open Theatre

to develop plays collectively, through ensemble workshop improvisation, and dramatize them ritualistically, with nonverbal sound and choreographed movement as well as words, according to Chaikin’s post-method, post-absurd theories on acting technique. Their first production was Terry’s Viet Rock (May, 1966)—the first American rock musical, the first play to protest the undeclared war, and the inspiration for the American Tribal Love-Rock Musical, Hair. The second was the fabled farce, America Hurrah (November, ’66), which slapped the face of the nation and knock it for a loop.

America Hurrah is a sardonic trilogy of three short plays related only by their cultural absurdity. “Interview” parodies four Interviewers and four Applicants for jobs in simultaneous, crisscross, repetitive Q & A, revealing their thoughts in direct asides to the audience, and building to a cacophonous climax, after which all exit to a busy street and disperse to assume their roles in other equally absurd encounters; “TV” is a real-life soap opera played on half the stage while the other half is a TV set, where actors enact TV westerns, news broadcasts, and commercials that compete for audience attention; “Motel” is three giant, grotesque human puppets: one the Motel Owner, who busies herself about mechanically as her recorded voice welcomes the Man and Woman, chattering cordially as both disrobe, demolish the room, simulate sex, and tear the Owner limb from limb.

This play was the first to attack the American Dream directly, thereby aligning the company with the counterculture and arousing the attention J. Edgar Hoover, who saw fit to line the streets with agents, in case of riots (and to spy on the players). This naturally made headlines, and the play packed the house for 648 performances.

The Second City

By the early ’60’s, regional theaters were presenting more new plays than Broadway, many of which were subsequently restaged there and won Tony awards. Among the best were the Guthrie in Minneapolis, The Alley in Dallas, the Arena in Washington, the Pasadena in California, the Goodman in Chicago, and the Actors of Louisville—all presenting standard, mostly commercial plays and musicals. The revolution bubbled up in the city second only to New York in skyscrapers.

In the summer of 1955, at The Compass bar in Hyde Park, University of Chicago students David Shepherd and Pail Sills, began creating a commedia dell’arte based on professional theater games developed and taught by Paul’s mother, Viola Spolin, the Mother of Improvised Drama.

The term refers to wandering troupes of players in 16th and 17th Century who improvised lines and business off the tops of their heads to embellish a barebones scenario—like storytellers. While Stanislavsky recommended playing games for insights in rehearsal, never before and never after had improv been a form of drama.

Spolin was a social worker with WPA who worked with inner-city and immigrant children by creating and playing games that focused on individual creativity, adapting and focusing the concept of play to unlock the individual’s capacity for creative self-expression. Later, she moved from children to adults playing therapeutic roles, while Paul, the actor, linked her work to Stanislavsky with his improv troupe, The Second City, playing “theatre games” for crowds in Old Town to this day.

These games demonstrated the profound recognition that indeed, as Shakespeare so aptly put it, “All the world’s a stage/And all the men and women merely players.” Life’s a game, and every move we make is improvised. In performance, for the first time in centuries, Second City players Sills, Shepherd, Shelley Berman, Mike Nichols, Del Close performed on stage to launch a new dramatic genre that spread like wildfire, in cabarets and coffee shops, night clubs and concert halls, culminating in the 1975 premiere of Saturday Night Live, a virtual clone that often starred Second City players; e.g. Gilda Radner, John Belushi, Dan Aykroyd, Bill Murray, Del Close, John Candy, Mike Myers, Steve Carell, Tina Fey, Amy Poehler, Chris Farley, and Stephen Colbert.

Meanwhile, in 1973, Spolin assembled more than 200 of her games and published them in Improvisation for the Theatre, which at once became a core text for all aspiring actors and directors, school teachers, social workers, corporate trainers, and psychoanalysts world wide.

The Connection

In 1963, several Second City players carried the concept to the west coast as The Committee and upped the stakes, from trivial fun and games to counterculture politics. Soon young hipsters lined the block and packed the 300-seat storefront theatre on San Francisco’s Broadway thirteen times a week to experience “guerilla theatre” (so-called to remember their revolutionary idol, Che Guevara) with games that ridiculed and blistered the American Dream. Other nights and days they played the streets, attracting crowds with caustic wit and lewd, profane, and anti-American obscenities that sometimes led to riots and landed them all in jail.

Notoriety rewarded them with larger crowds, and in 1968 they opened a sister troupe in Los Angeles on Sunset Strip, which drew the attention of Dick Cavett. Their numerous appearances on his late night talk show introduced the public to the games, and soon the new form was the rage.

Proliferation

After America Hurrah, while mainstream theatre continued to dominate Broadway, Off Broadway, and all the not-for-profit entities all over the country, experimental works enjoyed a surge of popularity, first among savvy theatergoers around New York, then elsewhere, in accordance with the turbulent times—especially among the young, now face to face with death for no good cause. Those among them who leaned left grew long hair, wore love beads, burned their draft cards, and joined movements to challenge the Establishment, protest and demonstrate.

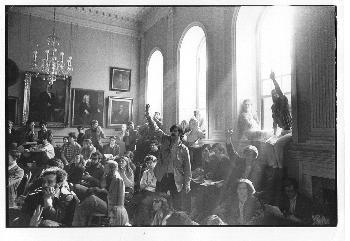

Before long every college campus had its coterie of long-haired, braless “hippies” who used their educated skills to make their feelings known. Rallies, concerts, exhibitions, editorials, lectures, and performing arts all railed against the status quo, with drama at the forefront.

Student actors played off-off-Broadway scenes, learned Method Acting, Improv, and Open Theatre techniques; student playwrights threw away the rules. If nothing mattered, they were free to think outside the box, to “boldly go where no man has gone before.” The result was a kaleidoscope of independent visions of the post-modern world, each with its unique, personal blend of genre, subject, structure, technique, style, language, mood, and meaning (or lack thereof). Their one consistent thread: the recognition of futility.

This trend to collective individualism spread from colleges to coffee houses, storefronts, legitimate theaters, some even to Broadway, where they spiced up the mainstream with unexpected shockers, no one like another. The first of these defines the next dramatic Moment.

Moment #12: Hair

The 1967 “Summer of Love” came to New York in October, when Joe Papp dared to launch his Public Theatre with the play that consolidated all the youthful protests of the time into “The American Love-Rock Musical” that knocked the country off its feet.

Dramatic art would never be the same.

The Team

The writers, young James Rado and Gerome Ragni, met as actors in an Off Broadway flop in 1964, hit it off, and set to work on a script about long-haired hipsters. Rado was a naïve, upper class actor/musician who wrote Rodgers and Hammerstein style musical reviews in college, then studied method acting with Lee Strasburg. Ragni, on the other hand, a low-born Italian-American hippie, was mentored by Joe Chaikin. Two years later he helped create and played a lead in the Open Theatre production of Viet Rock—a major influence on the structure and eclectic style of Hair.

Add to these jazz-pop composer, Galt McDermott—well over thirty, short hair, married with four kids and living on Staten Island, who had “never even heard of hippies” before Hair—and the eclectic hodge-podge of musical and dramatic elements that comprise this “American Tribal Love-Rock Musical.”

Dramatically, Hair is a potpourri of forms that range from Dionysian ritual to tragedy, to satire, comedy, romance, a little Shakespeare, social Realism, anti-Real, and the Absurd, and features methods gleaned from Stanislavski, the Becks, Joe Chaikin, and Viola Spolin/Paul Sills. The 30-song score runs the gamut of modern musical types, from hard rock to folk ballad, each distinct from the rest, in music matched to words and feelings regarding a particular—controversial—cultural theme.

Plot & Theme

While the play is mostly in the songs, the story line that ties them together is all about Claude, the charismatic leader of a diversified “Tribe” of politically active, long-haired hippies living a bohemian life in New York City and fighting against conscription into the war. Claude, his good friend Berger, their roommate Sheila, and their friends struggle to balance their young lives, loves, and the sexual revolution with their rebellion against the war, their conservative parents, and the Establishment—much of the second act is a hallucinatory vision of these horrors. Ultimately, Claude is called up, and must decide whether to resist the draft as his friends have done, or to succumb to the pressures of his parents (and conservative America) to serve in Vietnam, compromising his pacifist principles and risking his life.

The overarching theme is the absurd tragedy of the war—Claude’s choice “to be or not”; to live in fear or die in Viet Nam. Songs by others in the Tribe dealt personally or collectively with issues ranging from flaws in the system to hope for the future. Their attitudes toward sex, race, drugs, nudity, God and country, life on earth—the earth itself, its meaning—were all too much for any producer on or Off Broadway, and the team was on the verge of breaking up and moving on.

Serendipity

By miraculous coincidence, Joe Papp was (also) on the verge of completing the conversion of his old hotel into The Public Theatre, his mission to produce new plays that imagined drama more that Broadway entertainment—for art instead of profit. He was reading scripts in search of a provocative, off-beat, anti-Broadway play for the grand opening. He had seen Viet Rock the year before and met Ragni, who gave him a script, which joined the pile at the bottom. Only a chance meeting on the subway gave the writer the chance to pitch the project. The rest is history.

The Age of Aquarius

Hair opened at the Public October 17, 1967, for a limited six-week, sold out run that led to six more weeks at the off-off Cheetah Club, after which it was reworked for a Broadway opening at the Biltmore, April 29, ’68, where it played 1,750 performances over the next four years, toured the country, and became an international sensation. The original cast album was the Number One Hit on Billboard for fourteen consecutive weeks; its psychedelic opening anthem to “The Age of Aquarius,” the Number One single for six.

More to the point, Hair introduced Broadway and the world to the “hip” Greenwich Village culture of the Aquarian “Tribe”—the hair, the dress, the attitudes (sex, drugs, rock & roll), and secular values (peace and freedom, equal justice, hope, and love)—that became the public face and the unifying lifestyle of hippie movements everywhere.

The time was ripe for revolution. During Hair‘s Off Broadway run, the Tet offensive in Vietnam demoralized US troops and Martin Luther King was assassinated; the week after its Broadway opening, Sirhan Sirhan killed Bobby Kennedy, which led directly to the riots in Chicago two months later and the subsequent election of Richard Nixon. Protests grew in size and number with the body count, as people were made aware of the absurdity, not only of the war, but of all the fatal flaws in the American Dream and the World itself—from WASP-driven discriminations and persecutions to the end of humankind, whether by nuclear explosion (or meltdown) or environmental pollution, or pandemic virus, asteroid (or comet), alien invasion . . .

Sadly, the moment passed.

The Nixon Years

By 1969, nearly half a million American troops were deployed in Vietnam, more than 30,000 had been killed, and patience at home was wearing thin. Most Americans opposed the war by then, but didn’t want to lose it, so they elected Nixon, who promised his “Moral Majority” he’d win or end it “honorably”—neither of which did he do. Instead, he pacified the pacifists by withdrawing American troops and doubling down on relatively risk-free air support, laying waste not only to North and South Vietnam, but also to neighboring Laos and Cambodia. To please the hawks, he bashed the peaceniks from his bully pulpit and ordered the FBI to undermine their cause.

The cause—bolstered now by celebrated artists, writers, and performers, scientists, educators, many men of God, and a few brave politicians—argued that the problem with the Establishment was the Establishment itself, the solution for which could be found only in the “harmony and understanding, sympathy and trust” of the Age of Aquarius.

1969

On January 28—eight days after Nixon’s inauguration—an off-shore well blew out, spewing oily goo 90 feet in the air and spilling four million gallons over the next eleven days, polluting 35 miles of Santa Barbara coastline. This event was among the first and by far the worst such spill for decades, and remains third worst in US history. An auspicious beginning.

On the plus side, it triggered environmentalists to add their cause to the protest movement that, by the end of the year, resulted in the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency. A win for the Good Guys.

On April 9, dozens of Harvard students occupied University Hall to demand the abolishment of the ROTC program. Such protests were to become routine on college campuses throughout the war.

What next?

On July 8, Nixon withdrew 35,000 American troops from Vietnam.

And the Manson Family murdered Sharon Tate & friends in Los Angeles.

Twelve days later the Eagle landed on the moon.

Late in August, a half million hippies congregated in the Catskills for an aptly-named “Aquarian Exposition: 3 Days of Peace & Music,” also known as Woodstock. Good guys. And on November 15, a nationwide moratorium on the war saw millions of Americans young and old—students, working men and women, school children—boycott jobs and classes to participate in anti-war activities. The tide was turning.

But on December 6, the Altamont Speedway Free Festival in California, promoted as “Woodstock West,” turned into a bloody brawl.

The year ended with the withdrawal of another 50,000 troops.

Vietnamization

The next three years of the war played out in Living Color on TV, with all its atrocious horrors, all around the nation and the world. The world was horrified. What had begun among the young became a groundswell of protests and demonstrations, marches, clashes with police and soldiers—also on TV. Politicians, pressured by constituents, pressured Nixon to fulfill his promise and wind it up. He saved face with “Vietnamization,” a clever policy he hoped would appease them. In essence, it reduced the number of GIs based in country, leaving the ground war to the natives, while continuing to show strength from the air.

In 1970, he withdrew 150,000 troops; 65,000 more in ’71; by November, ’72, only 16,000 Army advisors remained in country. He then ordered twelve straight days (December 18-29) of the most intensive bombing of the war, with waves of B-52s dropping more than 100,000 bombs on Hanoi and Haiphong.

And on January 29, 1973, he abolished the draft—to the huge relief of American boys and the people who loved them.

By that time 2.7 million has served at least one 13-month tour of duty in Vietnam, 58,000 of whom were killed (one in 46), died, and 150,000 (one in 18) were wounded. Compared to the 4,000,000 North and South Vietnamese soldiers and civilians dead or wounded (and millions more displaced), Americans came out far ahead—twenty to one.

But Vietnam won the war.

Election Year

1972 was a banner year for Nixon on the world scene, from his January announcement of the Space Shuttle program to cooling down the Cold War, first with his unprecedented eight-day visit with Chairman Mao in February, then, in May, with Soviet leader Brezhnev, where they signed the groundbreaking Strategic Arms Limitation (SALT) Treaty.

The home front was another story.

With all the boys back from the war, the focus of the Movement shifted from life or death to moral (and economic) condemnation of a nation that continued to waste billions dropping bombs on innocent people (who were, after all, just fighting for their freedom), but to ignore the gross inequities that carved its citizens up into groups according to a multitude of discriminatory factions that too often fought among themselves.

Watergate

On June 17, 1972, five burglars were caught ransacking the offices of the Democratic National Convention Headquarters at the Watergate Hotel in Washington, and the nation turned its attention form the war to the scandal in the White House—once again on the same opposing sides, preponderately (at first) the Establishment and others who refused to believe the President was a crook. He won re-election 49-1.

On the other side stood the Democrats, the liberal intelligentsia, and the hippies, whose many divers causes, no longer focused on the War, found common cause in Nixon. If they could force him out of office, it would be “like, man, like, a coup, like—wow!” All their problems would be solved.

As time went by, evidence uncovered by Washington Post journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein demanded official investigation, and on May 17, 1973— eleven months after the break-in—American’s tuned in live to witness the first in a year’s worth of hearings conducted by the U. S. Senate Watergate Committee, the truly honorable North Carolina “Senator Sam” Irvin presiding. Evidence and testimony ultimately determined Nixon was a crook, and on August 8, on live TV, he became the first American President to resign.

If only there had been a leader. Every revolution needs a leader, some one person recognize by all to be the one to know they way, the hero, the statesman, the radical—the one to follow. George Washington. Simon Bolivar. Joan of Arc. Lenin. Sun. Mao. Castro. Ho Chi Minh. (No Hitler, please. Nor Mussolini, Stalin, Attilla the Hun, nor Trump.)

The problem was their greatest strength: diversity. No one among them was like all of them. Each cause was organized within itself, with national leadership and chapters everywhere, but never was a coalition formed to recognize their only universal commonality. We’re all human beings.

There were attempts. In 1972, hippie activists Barry Plunger and Garrick Beck (son of Julian) formed the Family of Living Light and held its first World Rainbow Gathering—a 4-day Woodstock redo—to celebrate the 4th of July in Granby, Colorado, near the sacred Table Rock. The Family, a back-to-nature hippie tribe, invited any and all from anywhere who shared a fundamental ideology of peace and harmony, truth and justice, freedom, and respect, to Strawberry Lake for three days of sex, drugs, rock & roll, and political soap box revolution on the Fourth of July. “Bring if you can, as much as you can, but nothing to sell,” was their slogan, and the invitation was open free of charge (no money was permitted) to share experiences, love, dance, music, food, and learning, and to pray for world peace.

This organization still exists, hosting one official World Gathering a year and harboring a number of independent affairs all around the globe. They last from four days to six weeks (in Israel, in 1992), and draw as many as 20,000 back-to-nature peaceniks.

They don’t get a lot of press.

More familiar is Fred Hampton’s 1969 Rainbow Coalition of black, brown, red, and yellow, later under the umbrella of Jesse Jackson’s more tolerant Rainbow/PUSH. Today humanity is covered in the U.S. by the American Humanist Association, a non-profit organization promoting atheism, and the National Endowment for the Humanities, with an annual allotment of $162.25 million—0.00004% of the 4 trillion dollar national budget.

Aftermath

Meanwhile, the Revolution underwent a transformation, as hippie styles and customs attracted wannabees and profiteers, hangers-on who grew the numbers but sidestepped true commitment diluted the became the vogue and infiltration of wannabees and profiteers

absorbed in the culture,

backlash, political correctness

1981, AIDS throws a wrench in the sexual revolution.

y

My Lai

For this Moment, the world belonged to young idealists who believed in peace, love, freedom, joy, and music, whose war with the Establishment, like the Viet Cong against the US, . song hair was chic among the hip, and the world began turning against the war.